iCal Getting Slow When Showing a Different Day

Posted: 2014-October-9 Filed under: Computers | Tags: 10.6.8, Galaxy Player, iCal, iCal Dupe Delete, Mac Mini (mid-2010), MissingSync, OSX, Palm Pilot, Snow Leopard, SyncMate Leave a comment »So I've got a Macintosh Mini (mid-2010)—believe it or not, that's the official name—running "Snow Leopard" OSX 10.6.8. I synchronized a lot of data on that with a Galaxy Player 4.0 "YP-G1" (which I refer to as a "Palm Pilot" since it's shorter than saying "technically it's an MP3 player and not a smart phone", and since it replaced my Palm Vx which was in service for about 10 years.) I got frustrated with MissingSync for Android when it started flaking out and not connecting to the Palm Pilot anymore. I switched to SyncMate which I was very excited about (since, unlike MissingSync, it let me synchronize while charging.)

I started noticing that iCal was running slowly. Whenever I changed to a different day it would take around 4 seconds or so. I searched around and found iCal Dupe Deleter. It exports a backup for you in iCal then looks for duplicates and deletes them. Upon completion, you restore the fixed backup into iCal—a process which I assume replaces all your iCal data with the archive contents. I had 3 or 4 duplicates, but now iCal is (while not snappy) reasonably quick in switching between days. I only wonder if I simply created an archive in iCal with File > Export... > iCal Archive... then immediately restore it with File > Import... > Import... and picking the file I just created.

![]()

Trouble with OsmAnd's "Smart" Merge of Favorites.gpx

Posted: 2014-August-28 Filed under: Computers | Tags: Android, favorites.gpx, Galaxy Player, Google Maps, OpenStreetMap, org.apache.harmony.xml.ExpatParser, OsmAnd, Samsung, SGML Leave a comment »Years ago I was quite excited by an application for my Samsung Galaxy Player Android called OsmAnd. It is a free application (although you can buy a non-free version to support the project) that allows you to download OpenStreetMap data and use it like a GPS. It supports routing and talking directions like a commercial GPS, but, given its OpenStreetMap roots, if you find an error, you can edit it yourself and within days the changes will percolate to everyone's device.

One of the things I grew fond of was to directly edit the favorites.gpx file which contained all your "Favorite" places (now called "My Places" as of version 1.8). I could find a location in, say, Google Maps, then take the latitude and longitude and create an entry in favorites.gpx. The same time I upgraded to version 1.8, I stumbled upon a file with some old locations I had saved on my (now dead) Garmin GPS. I did some text manipulations and dropped them into the favorites.gpx file, but they wouldn't import.

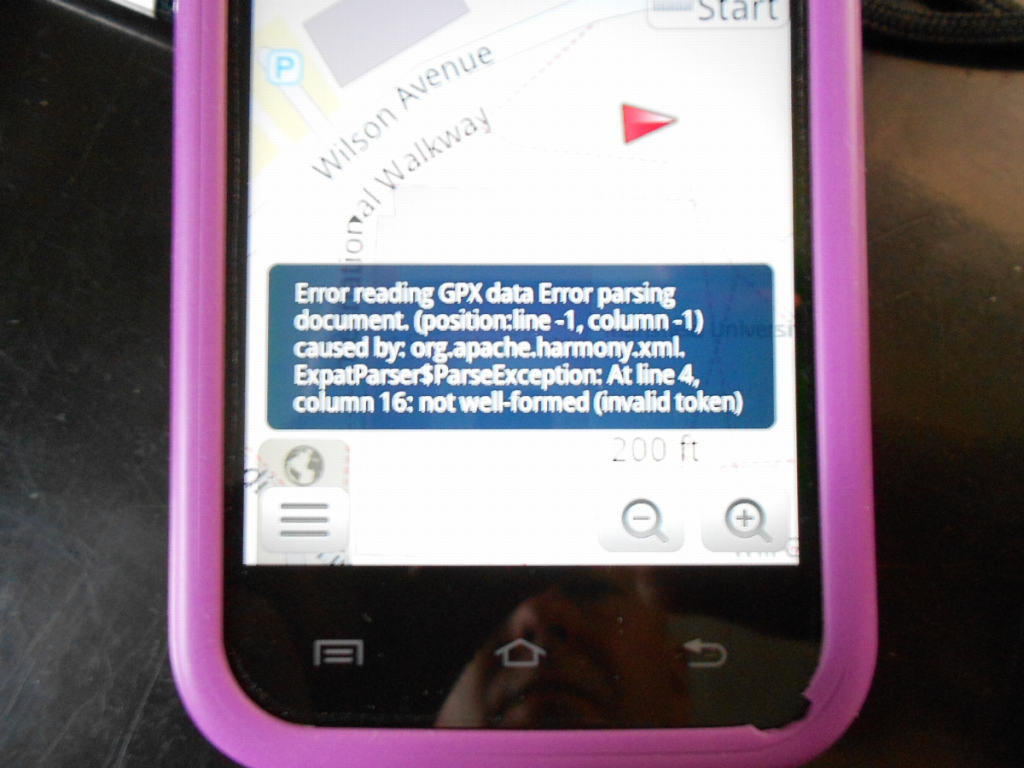

I played around with it for a while, and found that OsmAnd could open GPX files, with which it would try to import the entries. When I did that with favorites.gpx, it would read the file and ignore my new entries, replacing favorites.gpx with a version that did not contain any of the new entries. I didn't notice at the time, but it popped up a cryptic error message that thankfully led me to the problem:

The error reads "Error reading GPX data Error parsing document. (position: line -1, column -1) caused by org.apache.harmony.xml.ExpatParser$ParseException: At line 4, column 16: not well-formed (invalid token)". Examining that line in the favorites.gpx, I had attempted to include an ampersand (&) in one of the entries (the first one, as it turned out). Rather than coding it as the SGML entity (&) I simply included it in the text which the parser (validly) didn't like. Unfortunately OsmAnd didn't handle the error very gracefully.

While I appreciate the new "smart merge" feature, I debate the use of the word "smart" in the way my poorly-formed gpx file was handled!

![]()

About the FAX CSID/TSID on OSX 10.6.8 Snow Leopard

Posted: 2014-August-9 Filed under: Computers | Tags: AT-commands, CSID, CUPS, FAX, Hayes, Indigo iBook G3, Jaguar, OSX, PageSender, Snow Leopard, TSID Leave a comment »Call me a dinosaur. Here it is August 2014, and I am still using an Indigo iBook G3 running OSX 10.2.8 (Jaguar) on my home network because it can be used as a FAX machine. (And, well, for the approximately biannual Internet outage wherein I need to revert to dial-up and share the connection … which works surprisingly well for most day-to-day stuff. But I digress.) I've been running the long-discontinued PageSender software which was actually pretty nice, but the other day, it failed to bother to send a PDF. I figured it was a good idea to retire the iBook for its modem duties and just buy a USB modem. I opted for a USRobotics USR5637 56K USB Modem (from TigerDirect because I've been buying stuff from them since the 1990s).

It installed pretty easily and I was able to add it as a FAX modem per the System Preferences:Print & Fax page. One thing that I noticed was there was no place to enter the Called Subscriber ID (CSID) which is usually the same as the Transmitting Subscriber ID (TSID) and what I always thought was called the "Station ID" although my physical FAX machine's instructions simply refers to "Entering your name and phone number." In short, when you send a FAX, your phone number and TSID appear at the top of the page (and you can view the CSID of the FAX you just called). But in OSX 10.6.8 (Snow Leopard), there is only a space for "FAX Number".

My first reaction was to try and install PageSender to no avail: the installer failed to start on Snow Leopard.

So then I started digging. I started a free FAX account so I could experiment. I set the FAX number to my real FAX number and sent a FAX successfully. Both the FAX number and TSID appeared as that number. Next, I took a peek at the internal options: I opened a terminal session and (well, after some digging) entered:

defaults read /Library/Preferences/com.apple.print.FaxPrefs

Which resulted in:

{(my FAX number)

EmailFax = 0;

FaxNumber = ;(my default printer)

PrintFax = 0;

PrinterID = "";(my FAX receive folder)

ReceiveFaxID = "USRobotics_56K_Modem";

RingCount = 1;

SaveFax = 1;

SavePath = "";

"device-uri" = "fax://dev/cu.usbmodem0000001";

}

It appears, therefore, that there is no place to enter a proper CSID/TSID. Tinkering with the preferences again, I tried entering text into the FAX number field—assuming it was indeed a substitute for the CSID/TSID. Indeed, this replaced "FaxNumber" in my FaxPrefs.

I looked around for modem logs, but that wasn't an option … only some error logs existed which could be accessed through the wackadoodle CUPS HTTP interface. If you have OSX, you can probably link to http://127.0.0.1:631/ and muck around with things you probably shouldn't touch.

Another thought was to try setting the CSID directly in the FAX modem. Once upon a time, Hayes-compatible modems connected through RS-232 interfaces and had internal non-volatile memory to store settings, although back then, the S-registers could only contain one byte and it was rare to find more than tens of bytes of storage inside a modem. I found an old article on Apple.com which defined a clunky way to do it and it got me to access the modem. At first I couldn't see what I was typing, so I entered an ATE1 to enable command echo. Man, that takes me back … the first time I typed it was somewhere around 1987 and the last time was probably more than 20 years ago.

There exists a "standard" Hayes-compatible AT command +FLID="local ID" which is used to set the local ID in a TSI or CSI frame. But it's only supported with modems that have Class 2 FAX support: AT+FCLASS=? returns 0,1,8 which apparently means the USRobotics modem supports data (0), Class 1 FAX (1), and voice commands (8). The latter of which interestingly implies I could use it as an answering machine … maybe.

Now that I'm invested a couple hours in, I thought I'd crack open the modem's internal documentation. Indeed, it has no support for the +FLID command which I already confirmed. Alas, the AT commands appear to be a dead-end as well.

In the end, I decided to leave the modem alone and just use my FAX number as a station ID. It is sufficient and effective—and it certainly wasn't worth the hours of fooling around … but once I get started on a short project like this, I like to see it through to the end.

![]()

939 Days of Solar Power

Posted: 2014-June-27 Filed under: Solar | Tags: amps, avoided-cost rate, efficiency, energy, Iberdrola, insolation, photovoltaic, power, Renewable Portfolio Standard, RG&E, RPS, solar, SunPower, volts, watts Leave a comment »So the number is a bit random, but there you go. I officially had my solar system connected to the grid on December 1, 2011 … 939 days ago. Based on my usage at the time, I was eligible for tax breaks and grants for a system that could produce about 4,140 kWh a year. The way the math worked out on my house, that meant a 4,140 watt system. I also had to get it grid-tied which means that the electric energy produced from the solar system was to be mingled into the electrical grid; that means I don't have any batteries, and if the power goes out, I don't have power either—even if the solar system had energy available.

Here's some things I learned.

A Few Basics About Electricity

Well, first a basic lesson in electricity. Current is a flow of electrons; voltage is a potential difference between two points of a number of electrons available. If there is a voltage (measured in volts), making an electrical connection through a device allows that potential difference to flow making current (measured in amps). The amount of power (in watts) can be calculated by multiplying the voltage by the current. That power can be used to do work: work or energy is power multiplied by time.

For instance, it takes work to pedal a bicycle one mile; an average person can continuously produce about 100 watts of power. If jee travels 10 miles per hour, it would take 1/10 hours to go a mile, so jee would have exerted 10 watt-hours of energy, or you could say jee did 10 watt-hours of work. Calories are also units of energy (although confusingly food-calories are Calories which are kilocalories or 1000 work calories). Nonetheless, it's about 9 kilocalories of work. (For a sanity check, a cycling calculator indicated you'd burn about 30 kilocalories, and since you'd burn about 8 kilocalories in that time on a 2,000 Calorie-a-day diet, that's 17 kilocalories which is at least in the ballpark.)

Solar Panel Basics

Sorry, I digress. Photovoltaic solar panels convert light to electricity. A panel is usually rated for its power in watts which is calculated under specific conditions—typically something like 1,000 watts per square meter which is the maximum energy from the sun. However, at any point, there is a specific insolation (the amount of sunlight reaching that point.) At the equator during an equinox, the sun is directly overhead, and one square meter sitting on the surface gets the full square meter of solar energy. But if you imagine tilting that panel: once you get to 90 degrees, the sunlight is hitting the edge, and none of it actually strikes the surface, so you'd get zero power, so at angles between, there is some percentage of sun hitting the panel.

On earth, two things are happening: the earth is rotating and the sun is perpendicular to the earth only at one latitude. So as a day goes on, energy from the sun starts hitting one spot on the earth at a very shallow angle, which slowly increases during the day until mid-day when it is as close to perpendicular as it gets (based on latitude) and then gradually decreases until sunset.

The point is if you have a solar panel and it's mounted to your roof, it will only produce its rated power if the sun hits it straight-on. So for a 100-watt solar panel, the naive expectation is that for 8 hours of sunlight, it would convert 800 watt-hours of energy in a day. But because of the latitude adjustment and because of the rotation of the earth, you won't get anywhere close to that number. For instance, my best day around the solstice last year was June 18, 2013 with 26.31 kWh produced over about 16.5 hours or an average of 1,600 watts—barely 38% of the system's rated capacity. And on the best day around the winter solstice (December 28, 2013), the system produced only 4.67 kWh over about 10 hours or 467 watts on average—only 11% of the system's capacity (that day, the peak output was only 1,870 watts or 45% capacity).

And then there's cloudy days which I'm just going to totally omit.

Well, enough about solar panels for now …

My System

The installed cost was $23,240 or $5.61/watt. That's probably about typical. The solar panels alone were $13,000 and the grid-tie inverter was $2,000. All the hardware and wiring cost another $3,000, so the solar stuff alone was $18,000. Permits were almost $2,000, and labor was $3,000, making up the rest.

Installation Grant

If you live in New York State like I do and you look at your electric bill, there is a charge buried in the fees that is called the "Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) charge" which is described as "a state-mandated charge that funds renewable energy projects to achieve targets established by the Public Service Commission." I believe this is what funds the state-level grant. At the time I installed my system, they were offering $1.75 per installed watt, up to a maximum of 40% of the system installed cost. That meant a grant of $7,245. One thing that might change is to offer an incentive for buy-back of excess power at a generous rate—also from that same fund, and replacing the installation grant. This is what Canada does—they offer to buy power at a rate of over $0.50/kWh; at that rate, my system would net about $2,000 a year.

Tax Breaks

Next, there were some serious tax breaks. On the federal side, there was a 30% credit on the installed cost, and New York State offered a credit of 25%. That meant about $4,800 on federal and $4,000 on state. Those tax credits are a little weird and I'm glad I have an accountant to handle it: since I didn't have that much tax to pay in any one year, he figured out how to apply it over multiple years. So going back to the dollars, the whole system was $23,240 minus $7,245 from the RPS funds, and I had to come up with $16,000. Over the course of several years, I got tax breaks totaling $8,800, so in the end, I had to pay $7,200 for the system.

Additional Costs

However, there was another cost that was kind of hidden. The solar system had to be connected to my breaker box, but I didn't have enough open slots for new breakers to hook it up. I had to pay about $2,000 to get a new electrical panel installed and get a new wire run from the pole to my house. I could have gone with a 150-amp service, but it was only a hundred dollars more to go with 200-amps and allow for a lot of future expansion (if I had to replace the 150-amp box, it would be another $2,000).

A New Electric Meter

I also got a new electrical meter with a digital display. But it's really confusing since it cycles between "001", "002", "F", and all-segments on (the last two are apparently for testing.) There's a blinking arrow as well which points left when the system produces more than is being used, and energy is going back to the grid or right for when the usage is higher than the production and energy is being drawn from the grid. When it's drawing from the grid, that's accumulated on "001", and when it's adding to the grid, that's accumulated on "002". In theory if I were producing exactly what I was using, neither value would increase. If you do the math, you can't determine how much solar energy has been produced. However, an additional meter in the basement shows exactly that (it's another digital, but it's nothing to do with the gas and electric company).

So on December 1, 2011, it all got switched on, and I started adding energy back to the grid. Well, you saw the numbers for December … nothing going back to the grid.

Producing and Consuming Energy Throughout the Year

The way it works is what I like to think of as an energy bank account. My utility company, RG&E (well, actually Spanish company Iberdrola, but that's another story) keeps track of the electricity usage and generation. On months when the system produces more than usage, the surplus energy gets added to the "bank account". On months when the system produces less than usage, energy is first removed from the "bank account" until none is left, and I start having to pay again.

You'll hear from installers that RG&E will "buy back" your excess. So I was naively thinking they'd buy it at the same rate they sell it which would be nice—something like $0.11/kWh in the end. Well, they buy back at the uselessly-named "avoided-cost rate" which is (theoretically) what they pay to buy from the national grid. That is more like $0.05/kWh. This past year they bought back 347 kWh at (exactly) $0.04956232/kWh for a whopping $17.20 credit on my bill.

Now, if you do nothing, they'll buy back the energy on the month you activated the system. So in my case, they would take the surplus I built up all summer and pay out at $0.05/kWh, and then for the rest of winter when the system wasn't producing enough, I'd be paying for electricity. However, you can call your energy supplier and change your "credit date" to something more useful. I took a guess and figured that April or May would be a good time so I set it to that. It seems to work out because, like I said, I had a surplus of 347 kWh and have not had to pay for any electricity.

Another gotcha with this system is that RG&E charges a fixed "customer charge" for the privilege of being hooked up to the grid. Last month it was $21.38, and that's been pretty steady.

Online Monitoring

On another note, my system is through SunPower, so there's an online monitoring system. I have access to more information (and after some time figured out how to get them to e-mail me summarized data each month) but you can see my system here. My installer said I'd love it, but it's all powered by Adobe Flash, so it's actually kind of annoying and difficult to use. If you find this helpful and want a system of your own, there's always this link that gets me a cash kickback if you get a solar system through SunPower.

Summary

Since it's been enough time, I can do the math on my rate of payback. Well, I can get pretty close anyway.

According to the data from SunPower, in 2013, the system generated 3,949 kWh of electricity (or, you might think of it as averaging out to a 450-watt power plant, perhaps in comparison to the Ginna Nuclear Generating Station that supplies most of the Rochester area—which by similar calculation is a 560,000,000-watt power plant). Based on data from RG&E, my home consumed 2,432 kWh from the grid and added 2,694 kWh to it. So supposedly of the 3,949 kWh the system produced, 2,694 kWh went back to the grid, leaving 1,255 kWh consumed in the house. Since I drew 2,432 kWh from the grid as well, that totals 3,687 kWh consumed. That leaves an excess of 262 kWh which is pretty close to the 347 kWh from my last bill.

Back in 2011 I was on ConEd's Green Power which was costing around $0.095/kWh with taxes and everything (but not counting the monthly charge which would have equated to $0.158/kWh). So just looking at the base cost of electricity, that's $583 in saved usage and $17 in extra production or an even $600 total. In the end, I paid $7,200 for the system, so assuming 2013 is an average year and electricity rates stay the same, it pays for itself in about 12 years. Of course, if the cost of electricity doubled, that means the system pays off in half the time. Nonetheless, having the capacity to generate electricity is a boon no matter what. And if you factor in the added value to the home, the system kind of pays off instantly.

But money isn't my motivation in this. I liked the idea of being part of a group getting us away from fossil fuel and nuclear usage. And if you figure the electricity I use is mostly produced just a few feet from where it's used. The U.S Government claims only 6% is lost from production to consumption, but I find that hard to believe as a typical high-power transformer is about 97% efficient, and at least four are needed from a generator to a household, so that's 89% efficient or an 11% loss. In any case, eliminating much of the grid offers possible gains in efficiency.

Addenda

June 27, 2014: Added the kickback link and wanted to mention that the ridge of my house runs almost due north-south, so my solar panels are actually installed on the west-facing side. While a better orientation, or a tracking system would use the panels more efficiently, there's also the factor of cost, and to be honest, it's not that big a gain to orient them differently.

August 9, 2014: Did a few grammar edits and added the bit about being a power plant.

Marcy 15, 2015: My payback period was way off so I recalculated the numbers and fixed it.

![]()

Use used coffee grounds to wash grease from your hands.

Posted: 2005-December-24 Filed under: Cleaning Leave a comment »Wash your hands with a mixture of a small pinch of used coffee grounds with ordinary dish soap to remove grease.

![]()

Strengthen screw holes using a twist-tie.

Posted: 2005-December-24 Filed under: Wood Leave a comment »Remove the loose screw, bend a twist-tie in half, and stick the bend corner into the hole. Cut it off with scissors, leaving a hole's-width sticking out. Bend the two protruding ends opposite one another, flush to the surface. Screw the screw in again — the thickness of the twist-tie will help keep the screw from pulling out.

![]()

Wipe toilet seats with a small amount of toilet paper.

Posted: 2005-December-24 Filed under: General Leave a comment »If you need to use any "unfamiliar" toilet (public or just at a someone's house) make a habit of grabbing a couple sheets of toilet paper first and wiping down the seat. That way you'll never sit on a wet seat and you'll know in advance that there is toilet paper.

![]()

Before putting your hands on bare wires, short them out first.

Posted: 2005-December-24 Filed under: Electrical Leave a comment »When you work on any in-wall electric circuits, shut off the power at the breaker. When you're absolutely sure the power is off, short out the wires using a screwdriver. If you have done everything correctly, nothing will happen; otherwise, a shower of sparks will indicate your error rather than you being electrocuted.

![]()

When working on an appliance, put the plug in your pocket.

Posted: 2005-December-24 Filed under: Electrical Leave a comment »Make a habit of putting the plug of any appliance you're working on into your pocket. That way, you'll be less likely to accidentally work on it when it's plugged in.

![]()

Use 3-sided tomato cages to make signs to stick in the ground.

Posted: 2004-June-7 Filed under: General Leave a comment »If you're having a yard sale or just want to make a sign, an easy method is to use 3-sided tomato cages that fold flat. Unfold the cage and put your sign inside. Tape it in place across some of the wires to keep it from sliding up-and-down then fold the cage sides back onto the surface to keep it locked in place.

![]()

Recent Comments